My Hero Academia Eraserhead Girlfriend and Joke Concept Art

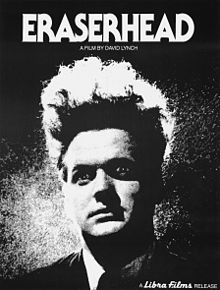

| Eraserhead | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lynch |

| Written by | David Lynch |

| Produced past | David Lynch |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | David Lynch |

| Music past |

|

| Product | AFI Centre for Advanced Studies |

| Distributed by | Libra Films |

| Release engagement |

|

| Running fourth dimension | 89 minutes[one] |

| State | U.s.a. |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $vii 1000000[2] |

Eraserhead is a 1977 American surrealist horror film written, directed, produced, and edited past David Lynch. Lynch besides created its score and sound design, which included pieces by a diverseness of other musicians. Shot in black and white, it was Lynch's outset feature-length endeavour following several short films. Starring Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, Jeanne Bates, Judith Anna Roberts, Laurel Well-nigh, and Jack Fisk, it tells the story of a man who is left to care for his grossly deformed child in a desolate industrial landscape.

Eraserhead was produced with the aid of the American Film Plant (AFI) during Lynch's time studying there. It nonetheless spent several years in principal photography considering of funding difficulties; donations from Fisk and his married woman Sissy Spacek kept production adrift. It was shot on several locations owned past the AFI in California, including Greystone Mansion and a gear up of disused stables in which Lynch lived. Lynch and sound designer Alan Splet spent a twelvemonth working on the film's sound afterward their studio was soundproofed. The soundtrack features organ music past Fats Waller and includes the vocal "In Sky", written and performed for the film by Peter Ivers, with lyrics by Lynch.

Initially opening to modest audiences and little interest, Eraserhead gained popularity over several long runs as a midnight movie. Since its release, it has earned positive reviews and is considered a cult motion-picture show. Its surrealist imagery and sexual undercurrents have been seen every bit key thematic elements, and its intricate sound design as its technical highlight. In 2004, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry every bit "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3]

Plot [edit]

The Man in the Planet (Jack Fisk) is moving levers in his home in space, while the head of Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) floats in the sky. A spermatozoon-like creature emerges from Henry's oral cavity, floating into the void.

In an industrial cityscape, Henry walks home with his groceries. He is stopped outside his apartment by the Beautiful Girl Beyond the Hall (Judith Anna Roberts), who informs him that his girlfriend, Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), has invited him to dinner with her family unit. Henry leaves his groceries in his apartment, which is filled with piles of dirt and expressionless vegetation. That night, Henry visits Mary'south home, conversing awkwardly with her mother. At the dinner table, he is asked to carve a chicken that Mary'southward father has "made"; the bird moves and writhes on the plate and gushes blood when cut. Later on dinner, Henry is cornered by Mary's female parent, who tries to kiss him. She tells him that Mary has had his child and that the 2 must ally. Mary, however, is non sure if what she bore is a child.

The couple move into Henry's 1-room flat and begin caring for the child—a swaddled package with an inhuman, snakelike face, resembling the spermatozoon brute seen earlier. The infant refuses all food, crying incessantly and intolerably. The sound drives Mary hysterical, and she leaves Henry and the kid. Henry attempts to treat the kid, and he learns that information technology struggles to breathe and has developed painful sores.

Henry begins experiencing visions, once again seeing the Homo in the Planet, besides as the Lady in the Radiator (Laurel Nigh), who sings to him as she stomps upon miniature replicas of Henry's child. Afterwards a sexual encounter with the Cute Girl Across the Hall, Henry has another vision, seeing his own caput autumn off, revealing a stump underneath that resembles the child'south face. Henry's head falls from the sky, landing on a street and breaking open. A boy finds it, bringing information technology to a pencil mill to be turned into erasers.

Awakened, Henry seeks out the Beautiful Daughter Beyond the Hall, simply finds her with another human being. Crushed, Henry returns to his room. He takes a pair of scissors and for the first time removes the child's swaddling clothes. It is revealed that the child has no peel; the bandages held its internal organs together, and they spill apart after the rags are cut. The kid gasps in pain, and Henry stabs its organs with the scissors. The wounds gush a thick liquid, roofing the child. The power in the room overloads, causing the lights to flicker; equally they pic on and off the child grows to huge proportions. As the lights burn out completely, the child's head is replaced past the planet seen at the beginning. Henry appears amidst a billowing cloud of eraser shavings. The side of the planet bursts apart, and inside, the Homo in the Planet struggles with his levers, which are now emitting sparks. Henry is embraced warmly by the Lady in the Radiator, as both white light and white dissonance build to a crescendo before the screen turns black and silent.

Product [edit]

Pre-production [edit]

Writer and director David Lynch had previously studied for a career as an artist, and he had created several curt films to animate his paintings.[4] By 1970, however, he had switched his focus to film-making, and at the historic period of 24 he accustomed a scholarship at the American Flick Institute's Heart for Advanced Movie Studies. Lynch disliked the course and considered dropping out, but later being offered the chance to produce a script of his own devising, he changed his listen. He was given permission to employ the school's entire campus for movie sets; he converted the school's disused stables into a serial of sets and lived there.[5] In improver, Greystone Mansion, also owned past the AFI, was used for many scenes.[6]

Lynch had initially begun work on a script titled Gardenback, based on his painting of a hunched effigy with vegetation growing from its back. Gardenback was a surrealist script almost adultery, which featured a continually growing insect representing one human's lust for his neighbor. The script would take resulted in a roughly 45-minute-long motion-picture show, which the AFI felt was too long for such a figurative, nonlinear script.[7] In its place, Lynch presented Eraserhead, which he had developed based on a daydream of a man's head being taken to a pencil factory past a pocket-size boy. Several lath members at the AFI were notwithstanding opposed to producing such a surrealist work, just they acquiesced when Dean Frank Daniel threatened to resign if information technology were to be vetoed.[eight] Lynch's script for Eraserhead was influenced by his reading equally a picture student; Franz Kafka's 1915 novella The Metamorphosis and Nikolai Gogol'due south 1836 short story "The Olfactory organ" were potent influences on the screenplay.[9] Lynch also confirmed in an interview with Metro Silicon Valley that the film "came together" when he opened upward a Bible, read one verse from it, and shut information technology; in retrospect, Lynch could not remember if the verse was from the Old Attestation or the New Testament.[10] In 2007, Lynch said "Believe it or not, Eraserhead is my most spiritual flick."[11]

The script is also thought to have been inspired past Lynch's fear of fatherhood;[6] his daughter Jennifer had been born with "severely clubbed feet", requiring all-encompassing corrective surgery as a child.[12] Jennifer has said that her own unexpected conception and nascency defects were the footing for the film'due south themes.[12] The picture'south tone was also shaped past Lynch's time living in a troubled neighborhood in Philadelphia. Lynch and his family spent five years living in an atmosphere of "violence, hate and filth".[13] The area was described as a "offense-ridden poverty zone", which inspired the urban properties of Eraserhead. Describing this menses of his life, Lynch said, "I saw so many things in Philadelphia I couldn't believe ... I saw a grown woman grab her breasts and speak like a babe, complaining her nipples hurt. This kind of thing will set you back".[6] In his book David Lynch: Cute Night, film critic Greg Olson posits that this time contrasted starkly with the director'southward childhood in the Pacific Northwest, giving the director a "bipolar, Sky-and-Hell vision of America" which has subsequently shaped his films.[13]

Initial casting for the film began in 1971, and Jack Nance was rapidly selected for the lead role. Nevertheless, the staff at the AFI had underestimated the project's scale—they had initially green-lit Eraserhead subsequently viewing a xx-i page screenplay, assuming that the movie industry's usual ratio of one minute of film per scripted folio would reduce the film to approximately twenty minutes. This misunderstanding, coupled with Lynch's own meticulous direction, caused the moving-picture show to remain in production for a number of years.[5] In an extreme instance of this labored schedule, one scene in the film begins with Nance's character opening a door—a full yr passed earlier he was filmed entering the room. Nance, however, was dedicated to producing the moving picture and retained the unorthodox hairstyle his character sported for the entirety of its gestation.[14]

Filming [edit]

Buoyed with regular donations from Lynch'due south childhood friend Jack Fisk and Fisk's wife Sissy Spacek, production continued for several years.[15] Additional funds were provided by Nance's wife Catherine E. Coulson, who worked equally a waitress and donated her income,[16] and by Lynch himself, who delivered newspapers throughout the film's chief photography.[17] During one of the many lulls in filming, Lynch was able to produce the brusque movie The Amputee, taking advantage of the AFI's wish to test new movie stock before committing to bulk purchases.[18] The curt piece starred Coulson, who continued working with Lynch as a technician on Eraserhead.[xviii] Eraserhead 'due south production crew was very small, composed of Lynch; sound designer Alan Splet; cinematographer Herb Cardwell, who left the production for financial reasons and was replaced with Frederick Elmes; production managing director and prop technician Doreen Modest; and Coulson, who worked in a variety of roles.[xix]

It has been speculated that Lynch used a rabbit to create Spencer's alien-similar baby.

The physical effects used to create the deformed child take been kept surreptitious. The projectionist who worked on the film'southward dailies was blindfolded by Lynch to avoid revealing the prop's nature, and he has refused to discuss the effects in subsequent interviews.[20] The prop—which Nance nicknamed "Spike"—featured several working parts; its neck, eyes and mouth were capable of independent operation.[21] Lynch has offered cryptic comments on the prop, at times stating that "it was built-in nearby" or "maybe it was constitute".[22] Information technology has been speculated by The Guardian 's John Patterson that the prop may have been synthetic from a skinned rabbit or a lamb fetus.[23] The child has been seen as a forerunner to elements of other Lynch films, such as John Merrick's make-upwards in 1980's The Elephant Man and the sandworms of 1984'southward Dune.[24]

During production, Lynch began experimenting with a technique of recording dialogue that had been spoken phonetically backwards and reversing the resulting sound. Although the technique was not used in the film, Lynch returned to it for "Episode 2", the third episode of his 1990 idiot box series Twin Peaks.[25] Lynch also began his interest in Transcendental Meditation during the pic's production,[6] adopting a vegetarian nutrition and giving up smoking and alcohol consumption.[26]

Post-product [edit]

Lynch worked with Alan Splet to design the movie'due south audio. The pair arranged and fabricated soundproof blanketing to insulate their studio, where they spent near a year creating and editing the film's sound effects. The soundtrack is densely layered, including equally many as fifteen different sounds played simultaneously using multiple reels.[27] Sounds were created in a variety of ways—for a scene in which a bed slowly dissolves into a pool of liquid, Lynch and Splet inserted a microphone within a plastic bottle, floated it in a bathtub, and recorded the sound of air blown through the bottle. Afterward beingness recorded, sounds were further augmented past alterations to their pitch, reverb and frequency.[28]

After a poorly received test screening, in which Lynch believes he had mixed the soundtrack at as well high a volume, the director cutting twenty minutes of footage from the film, bringing its length to 89 minutes.[29] Amongst the cut footage is a scene featuring Coulson as the infant's midwife, some other of a human being torturing two women—i once again played past Coulson—with a auto bombardment, and one of Spencer toying with a dead cat.[30]

Soundtrack [edit]

| Eraserhead | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by David Lynch, Peter Ivers and Fats Waller | |

| Released | 1982 (1982) |

| Recorded | 1927, 1976 (1976)–1977 (1977) |

| Length | 37:47 |

| Label | I.R.S. |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Pitchfork Media | viii.8/10[32] |

The soundtrack to Eraserhead was released past I.R.Southward. Records in 1982.[33] The two tracks included on the album characteristic excerpts of organ music past Fats Waller and the song "In Heaven", written for the film by Peter Ivers.[34] The soundtrack was re-released on August 7, 2012, by Sacred Bones Records in a limited pressing of 1,500 copies.[35] The anthology has been seen every bit presaging the dark ambient music genre, and its presentation of background racket and non-musical cues has been described by Pitchfork 's Marking Richardson as "a sound track (two words) in the literal sense".[36]

Themes and analysis [edit]

Eraserhead 'southward audio design has been considered ane of its defining elements. Although the motion picture features several hallmark visuals—the plain-featured infant and the sprawling industrial setting—these are matched by their accompanying sounds, as the "incessant mewling" and "evocative aural landscape" are paired with these respectively.[37] The film features several constant industrial sounds, providing low-level background noise in every scene. This fosters a "threatening" and "unnerving" atmosphere, which has been imitated in works such as David Fincher's 1995 thriller Vii and the Coen brothers' 1991 black comedy Barton Fink.[37] The constant depression-level noise has been perceived by James Wierzbicki in his book Music, Sound and Filmmakers: Sonic Style in Movie theater as maybe a product of Henry Spencer'southward imagination, and the soundtrack has been described as "ruthlessly negligent of the deviation between dream and reality".[38] The film also begins a trend within Lynch'south work of relating diegetic music to dreams, equally when the Lady in the Radiator sings "In Heaven" during Spencer's extended dream sequence. This is also present in "Episode 2" of Twin Peaks, in which diegetic music carries over from a character's dream to his waking thoughts; and in 1986's Blue Velvet, in which a similar focus is given to Roy Orbison's "In Dreams".[38]

The movie has also been noted for its potent sexual themes. Opening with an epitome of formulation, the film and then portrays Henry Spencer every bit a graphic symbol who is terrified of, simply fascinated by, sex. The recurring images of sperm-like creatures, including the kid, are a abiding presence during the moving picture'south sex scenes; the apparent "girl next door" appeal of the Lady in the Radiator is abandoned during her musical number as she begins to violently smash Spencer'due south sperm creatures and aggressively meets his gaze.[39] In his volume The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, David J. Skal describes the film every bit "depict[ing] human reproduction as a desolate freak show, an occupation fit only for the damned".[40] Skal as well posits a different characterization of the Lady in the Radiator, casting her as "badly eager for an unseen audition's approval".[40] In his book David Lynch Decoded, Mark Allyn Stewart proposes that the Lady in the Radiator is in fact Spencer's subconscious, a manifestation of his own urge to kill his kid, who embraces him after he does so, as if to reassure him that he has done right.[41]

As a graphic symbol, Spencer has been seen as an everyman effigy, his blank expression and apparently wearing apparel keeping him a simple classic.[42] Spencer displays a pacifistic and fatalistic inactivity throughout the film, simply allowing events to unfold around him without taking control. This passive behavior culminates in his sole human action of instigation at the film's climax; his credible human activity of infanticide is driven by the domineering and controlling influences that aggress him. Spencer's passivity has also been seen past pic critics Colin Odell and Michelle Le Blanc as a precursor to Lynch's 1983–92 comic strip The Angriest Dog in the Earth.[43]

Release [edit]

Box office [edit]

Eraserhead premiered at the Filmex moving picture festival in Los Angeles, on March xix, 1977.[44] On its opening night, the picture was attended by twenty-five people; twenty-4 viewed it the post-obit evening. However, Ben Barenholtz, head of distributor Libra Films, persuaded local theater Movie house Village to run the motion picture as a midnight feature, where it continued for a year. Afterwards this, it ran for ninety-ix weeks at New York's Waverly Cinema, had a year-long midnight run at San Francisco'southward Roxie Theater from 1978 to 1979, and achieved a three-year tenure at Los Angeles' Nuart Theatre between 1978 and 1981.[45] The film was a commercial success, grossing $7 meg in the Us and $fourteen,590 in other territories.[2] Eraserhead was also screened equally part of the 1978 BFI London Film Festival,[46] and the 1986 Telluride Film Festival.[47]

Home media [edit]

Eraserhead was released on VHS on Baronial seven, 1982, by Columbia Pictures.[48] The film was released on DVD and Blu-ray by Umbrella Amusement in Australia; the former was released on August 1, 2009,[49] and the latter on May 9, 2012.[fifty] The Umbrella Entertainment releases include an 85-minute feature on the making of the film.[49] [50] Other dwelling media releases of the moving picture include DVD releases by Universal Pictures in 2001, Subversive Entertainment in 2006, Scanbox Entertainment in 2008,[47] and a DVD and Blu-ray release past the Benchmark Drove in September 2014.[51]

Reception [edit]

Upon Eraserhead 'southward release, Variety offered a negative review, calling information technology "a sickening bad-taste exercise".[52] The review expressed incredulity over the film'due south long gestation and described its finale as unwatchable.[52] Comparing Eraserhead to Lynch's adjacent motion picture The Elephant Human being, Tom Buckley of The New York Times wrote that while the latter was a well-made flick with an accomplished cast, the sometime was not. Buckley chosen Eraserhead "murkily pretentious", and wrote that the film'south horror aspects stemmed solely from the advent of the deformed kid rather than from its script or performances.[53] Writing in 1984, Lloyd Rose of The Atlantic wrote that Eraserhead demonstrated that Lynch was "1 of the nearly unalloyed surrealists always to work in the movies".[54] Rose described the flick as being intensely personal, finding that unlike previous surrealist films, such as Luis Buñuel'south 1929 piece of work United nations Chien Andalou or 1930's 50'Age d'Or, Lynch'south imagery "isn't reaching out to usa from his films; we're sinking into them".[54] In a 1993 review for the Chicago Tribune, Michael Wilmington described Eraserhead equally unique, feeling that the film'due south "intensity" and "nightmare clarity" were a result of Lynch'due south attending to item in its cosmos due to his involvement in so many roles during its production.[55] In the 1995 essay Bad Ideas: The Art and Politics of Twin Peaks, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote that Eraserhead represented Lynch's all-time work. Rosenbaum wrote that the director's artistic talent declined as his popularity grew, and assorted the film with Wild at Centre—Lynch's most recent feature picture at that time—saying "fifty-fifty the most cursory comparison of Eraserhead with Wild at Centre reveals an artistic decline then abrupt that it is hard to imagine the aforementioned person making both films".[56] John Simon of the National Review chosen Eraserhead "a grossout for cultists".[57]

Contemporary reception of the motion picture has been highly favorable. On Rotten Tomatoes, the moving picture holds an blessing rating of ninety% based on 62 reviews. The critical consensus reads, "David Lynch's surreal Eraserhead uses detailed visuals and a creepy score to create a bizarre and disturbing look into a homo'due south fearfulness of parenthood".[58] On Metacritic, the movie has a weighted average score of 87 out of 100 based on fifteen reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[59]

Writing for Empire magazine, Steve Beard rated the flick five stars out of 5. He wrote that it was "a lot more radical and enjoyable than [Lynch's] subsequently Hollywood efforts" and highlighted its mix of surrealist body horror and black comedy.[60] The BBC'due south Almar Haflidason awarded Eraserhead three stars out of five, describing information technology every bit "an unremarkable feat past [Lynch's] later standards".[61] Haflidason wrote that the motion-picture show was a gathering of loosely related ideas, adding that information technology is "so consumed with surreal imagery that there are almost limitless possibilities to read personal theories into information technology"; the reviewer'due south own take on these themes were that they represented a fearfulness of personal commitment and featured "a strong sexual undercurrent".[61] A reviewer writing for Film4 rated Eraserhead 5 stars out of five, describing it equally "by turns beautiful, annoying, funny, exasperating and repellent, but ever bristling with a nervous energy".[62] The Film4 reviewer wrote that Eraserhead was unlike nearly films released to that indicate, save for the collaborations between Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí; even so, Lynch denies having seen any of these earlier Eraserhead.[62] Writing for The Village Voice, Nathan Lee praised the film'southward use of sound, writing "to see the motion-picture show means null—i must also hear it".[63] He described the film's sound design as "an intergalactic seashell cocked to the ears of an acid-tripping gargantua".[63]

The Guardian 's Peter Bradshaw similarly lauded the motion-picture show, also awarding it five stars out of five. Bradshaw considered it to be a beautiful film, describing its audio blueprint equally "industrial groaning, as if filmed inside some collapsing factory or gigantic dying organism".[64] He compared it to Ridley Scott's 1979 film Alien.[64] Jason Ankeny, writing for AllRovi, gave the moving-picture show a rating of five stars out of five; he highlighted the agonizing sound design of the pic and described it as "an open up metaphor".[47] He wrote that Eraserhead "sets upward the obsessions that would follow [Lynch] through his career", adding his conventionalities that the film's surrealism enhanced the agreement of the director'southward after films.[47] In an article for The Daily Telegraph, motion-picture show-maker Marc Evans praised both the audio design and Lynch's ability "to make the ordinary seem so odd", considering the moving picture an inspiration on his own piece of work.[65] A review of the film in the aforementioned newspaper compared Eraserhead to the works of Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, describing information technology as a chaotic parody of family life.[66] Manohla Dargis, writing for The New York Times, called the film "less a straight story than a surrealistic aggregation".[24] Dargis wrote that the motion-picture show'southward imagery evoked the paintings of Francis Bacon and the Georges Franju 1949 documentary Blood of the Beasts.[24] Picture Threat 's Phil Hall chosen Eraserhead Lynch'due south all-time pic, believing that the director'due south subsequent output failed to live up to it.[67] Hall highlighted the flick's soundtrack and Nance's "Chaplinesque" physical comedy as the film's stand-out elements.[67]

Legacy [edit]

In 2004, Eraserhead was selected for preservation in the National Flick Registry by the United States Library of Congress. Choice for the Registry is based on a picture being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically pregnant".[3] Eraserhead was 1 of the subjects featured in the 2005 documentary Midnight Movies: From the Margin to the Mainstream, which charted the rising of the midnight motion picture phenomenon in the late 1960s and 1970s; Lynch took function in the documentary through a series of interviews. The production covers six films which are credited every bit creating and popularizing the genre; also included are Night of the Living Dead, El Topo, Pink Flamingos, The Harder They Come, and The Rocky Horror Picture Bear witness.[68] In 2010, the Online Film Critics Society compiled a list of the 100 best directorial débuts, listing what they felt were the all-time showtime-time feature films past noted directors. Eraserhead placed second in the poll, behind Orson Welles's 1941 Citizen Kane.[69]

Lynch collaborated with virtually of the bandage and crew of Eraserhead over again on after films. Frederick Elmes served as cinematographer on Blue Velvet,[70] 1988'south The Cowboy and the Frenchman, and 1990's Wild at Heart.[71] Alan Splet provided sound design for The Elephant Man, Dune, and Blueish Velvet.[72] Jack Fisk directed episodes of Lynch's 1992 television series On the Air [73] and worked as a production designer on 1999's The Straight Story and 2001's Mulholland Drive.[74] Coulson and Nance appeared in Twin Peaks,[75] and made further appearances in Dune,[76] Blue Velvet,[70] Wild at Heart,[77] and 1997's Lost Highway.[78]

Following the release of Eraserhead, Lynch attempted to find funding for his next project, Ronnie Rocket, a film "about electricity and a iii-pes guy with ruby hair".[79] Lynch met motion picture producer Stuart Cornfeld during this fourth dimension. Cornfeld had enjoyed Eraserhead and was interested in producing Ronnie Rocket; he worked for Mel Brooks and Brooksfilms at the time, and when the 2 realized that Ronnie Rocket was unlikely to find sufficient financing, Lynch asked to run into some already-written scripts to consider for his next project. Cornfeld found four scripts that he felt would interest Lynch; on hearing the title of The Elephant Man, the director decided to make information technology his 2d film.[80]

While working on The Elephant Human being, Lynch met American managing director Stanley Kubrick, who revealed to Lynch that Eraserhead was his favorite film.[81] Eraserhead likewise served as an influence on Kubrick's 1980 film The Shining; Kubrick reportedly screened the flick for the bandage and crew to "put them in the mood" that he wanted the film to reach.[82] Eraserhead is too credited with influencing the 1989 Japanese cyberpunk motion picture Tetsuo: The Iron Man, the experimental 1990 horror film Begotten, and Darren Aronofsky'due south 1998 directorial debut Pi.[83] [84] [85] Swiss artist H. R. Giger cited Eraserhead as "1 of the greatest films [he had] ever seen",[86] and said that information technology came closer to realizing his vision than even his own films.[87] Co-ordinate to Giger, Lynch declined to interact with him on Dune because he felt Giger had "stolen his ideas".[88]

See too [edit]

- List of films with longest product time

References [edit]

- ^ "Eraserhead (X)". British Lath of Film Classification. January 15, 1979. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Eraserhead – Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved Baronial 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Films Added to National Moving picture Registry for 2004" (Press release). Library of Congress. December 28, 2004. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 192–6.

- ^ a b Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Woodward, Richard B. (January fourteen, 1990). "A Dark Lens on America". The New York Times . Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Olson 2008, pp. 59–lx.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 54.

- ^ von Busack, Richard. "Diving In". Metro Silicon Valley . Retrieved Feb 25, 2017.

- ^ "David Lean Lecture: David Lynch". British University of Pic and Television Arts. October 27, 2007. Retrieved Feb 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Olson 2008, p. 87.

- ^ a b Olson 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. lx.

- ^ a b Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Patterson, John (September vi, 2008). "Movie: David Lynch's film has scarred many an innocent viewer, including a teenage John Patterson". The Guardian . Retrieved Baronial 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c Dargis, Manohla (December vii, 2007). "Distorted, Distorting and All-Also Human". The New York Times . Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, p. 234.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, p. 235.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Carlson, Dean. "Eraserhead [Original Soundtrack] – David Lynch / Alan R. Splet". AllMusic. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (August 9, 2012). "David Lynch/Alan Splet - Eraserhead". Pitchfork Media . Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Carlson, Dean. "Listen to Eraserhead by Original Soundtrack – Album Reviews, Credits, and Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved March xix, 2016.

- ^ "Eraserhead: Original Soundtrack Recording". Sacred Basic Records. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ Larson, Jeremy D (July 6, 2012). "David Lynch'southward Eraserhead soundtrack to receive deluxe reissue on Sacred Bones Records". Consequence of Audio. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (August 9, 2012). "David Lynch / Alan Splet: Eraserhead | Album Reviews". Pitchfork Media . Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ a b D'Angelo, Mike (May 14, 2012). "David Lynch shows how sound can be creepier than whatever prototype in Eraserhead". The A.V. Lodge. The Onion. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Wierzbicki 2012, p. 182.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 32.

- ^ a b Skal 2001, p. 298.

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 62.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, p. 215.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1991, p. 220.

- ^ "BFI | Movie & Idiot box Database | 22nd". British Pic Plant. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Ankeny, Jason. "Eraserhead – Review". AllMovie. AllRovi. Archived from the original on Jan 11, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ "New Video Releases". Billboard. 94 (31): 34. August 7, 1982. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Umbrella Entertainment – Eraserhead (DVD)". Umbrella Entertainment. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ a b "Umbrella Entertainment – Eraserhead (Blu-Ray)". Umbrella Entertainment. Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ "Eraserhead (1997)". The Benchmark Collection. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ a b "Variety Reviews – Eraserhead – Film Reviews – – Review by Variety Staff". Variety. 1977. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Tom, Buckley (October 17, 1980). "The Screen: 'Eraserhead'". The New York Times. p. C15.

- ^ a b Rose, Lloyd (October ane, 1984). "Tumoresque: the films of David Lynch". The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company. Archived from the original on May thirteen, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (November 19, 1993). "Eraserhead Makes Its Mark As A Monument To Alienation". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved Baronial 23, 2012.

- ^ Rosenbaum 1995, p. 23.

- ^ Simon 2005, p. 123.

- ^ "Eraserhead". Rotten Tomatoes . Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Eraserhead Reviews". Metatric . Retrieved November thirteen, 2021.

- ^ Beard, Steve. "Empire'due south Eraserhead Movie Review". Empire . Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Haflidason, Almar (Jan 16, 2001). "BBC – Films – review – Eraserhead". BBC. Retrieved Baronial 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "Eraserhead (1977) – Film Review". Film4. Channel Four Tv set Corporation. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Lee, Nathan (January nine, 2007). "David Lynch Made a Man Out of Me". The Village Voice. Village Voice Media. Retrieved Baronial 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Bradshaw, Peter (September 12, 2008). "Motion-picture show review: Eraserhead | Film". Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Evans, Marc; Monahan, Marker (Oct 5, 2002). "Film makers on film: Marc Evans". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Cheal, David (Oct 22, 2008). "DVD reviews: Charley Varrick, Iron Homo, Eraserhead, The Brusque Films of David Lynch, Festen 10th Ceremony Edition". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ a b Hall, Phil (February 10, 2006). "Flick Threat – Eraserhead (DVD)". Film Threat. Archived from the original on February viii, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Southern, Nathan. "Midnight Movies: From the Margin to the Mainstream – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards". AllMovie. AllRovi. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ "Online critics mail top 100 directorial debuts of all-time". The Contained. October half dozen, 2010. Retrieved Baronial 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, pp. 62–63.

- ^ "Alan Splet – Motion and Film Biography and Filmography". AllMovie. AllRovi. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 87.

- ^ "Jack Fisk – Move and Film Biography and Filmography". AllMovie. AllRovi. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 69.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Odell & Le Blanc 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 91.

- ^ Rodley & Lynch 2005, p. 92.

- ^ Lynch 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Roberts, Chris. "Eraserhead, The Short Films Of David Lynch". Uncut. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Harper 2007, p. 140.

- ^ Snider, Eric D (Apr 13, 2011). "What's the big deal?: Eraserhead (1977)". Movie.com. Archived from the original on January iii, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Vaughan, Robin. "Pi movie adds up to stimulating analysis." The Boston Herald. Herald Media Inc. October Ironh4, 2004.

- ^ Levy, Frederic Albert. "H. R. Giger - Conflicting Design" (PDF). littlegiger.com. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ Giger, Hans Ruedi (1993). HR Giger Arh+. Translated by Karen Williams. Taschen. ISBN978-3-8228-9642-6.

- ^ Alex. "HR GIGER WORKS WEEKENDS". vice.com. Retrieved Dec 25, 2012.

Sources [edit]

- Harper, Graeme (2007). The Unsilvered Screen: Surrealism on film (illustrated ed.). Wallflower Printing. ISBN978-1-904764-86-ane.

- Hoberman, J; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1991). Midnight Movies. Da Capo. ISBN0-306-80433-vi.

- Lynch, David (2006). Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity . Jeremy P. Tarcher Inc. ISBN978-0-641-91061-half dozen.

- Odell, Colin; Le Blanc, Michelle (2007). David Lynch. Kamera Books. ISBN978-i-84243-225-9.

- Olson, Greg (2008). Beautiful Dark (illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN978-0-8108-5917-3.

- Rodley, Chris; Lynch, David (2005). Lynch on Lynch (2nd ed.). Macmillan. ISBN0-571-22018-5.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathon (1995). "Bad Ideas: The Art and Politics of Twin Peaks". In Lavery, David (ed.). Total of Secrets: Critical Approaches to Twin Peaks (illustrated ed.). Wayne State University Press. ISBN0-8143-2506-8.

- Simon, John (2005). John Simon on Picture show: Criticism 1982–2001. Adulation Books. ISBN978-1-55783-507-ix.

- Skal, David J (2001). The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror . Macmillan. ISBN0-571-19996-viii.

- Stewart, Mark Allyn (2007). David Lynch Decoded. AuthorHouse. ISBN978-1-4343-4985-ix.

- Wierzbicki, James (2012). Music, Sound and Filmmakers: Sonic Mode in Movie house (illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-89894-ii.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eraserhead

0 Response to "My Hero Academia Eraserhead Girlfriend and Joke Concept Art"

Post a Comment