Dairy Farmers Are Left Behind Again

"Expect at that sweet heifer, high, tight udder, in her beginning lactation, idn't she sweet?" auctioneer Tom Bidlingmaier shouts as his son Cory plods and slips and pushes the moo-cow around a pen.

Watching information technology all are well-nigh 65 people, mostly men, by and large other small farmers in safe boots, standing in mud and manure as they murmur their bids. Ron Wallenhorst, the farmer auctioning off his herd of 64 milking cows, is pacing and borer an empty water bottle against his thigh. He has milked cows in his barn twice a 24-hour interval, every day, after taking over the farm from his father 32 years ago. Past the afternoon, all the cows will exist gone.

"This is our 401k," said Ron, 55 years quondam, his alpine frame yet hearty though he's 15 pounds lighter from stress.

The omens earlier the sale had non been great for Ron and his married woman Lori. A couple of weeks before, a few towns over from their own farm in Cuba Metropolis, Wisconsin, which is most 70 miles south-westward of Madison, they'd watched another complete dairy dispersal of a better herd. That means it produced more milk – 96 pounds (44kg) per moo-cow a solar day to the Wallenhorsts' 78 (35kg). The other farmer didn't brand out well financially. "We stood there with tears in our optics," Ron said. "Our whole life has been a risk. Deciding to sell was very, very difficult."

An 60 minutes before auctioneer Bidlingmaier started the bidding on the Wallenhorst herd, Lori was crying in a corner of the milk house. She wiped her eyes and stepped out into the morning. "That's a practiced sign," she said, motioning to the trucks rolling up with empty cow trailers fastened – they came to buy.

Four hours after, after the final cow is sold, the Wallenhorsts learn the herd went for $1,800 (£1,290) each, on average – relatively high for the region, and more than than Ron expected. He smiles for the first time that day, cracking open up a beer, finally part of the circle of relatives and neighbors who came non to buy but to support. Then, equally a squad of determined men coerced a moo-cow up on to its new owner's trailer, he teared upward and walked away.

With the Wallenhorst dairy subcontract gone, there'south but one left on the seven-mile stretch from ane side of town to the other; there were 22 when Ron was growing up in that location. "We worried no one would show upwardly because dairy farms are just disappearing in our area, and then at that place were fewer and fewer modest farmers to buy from the states," Ron said.

The license plates for Wisconsin say "America's Dairyland" beneath a moving-picture show of a red barn. The state has the most dairy farms in the country. Just it lost 826 dairy farms in 2019, or 10% of its dairy herds – the most dramatic loss in the country's history, and part of a downward trend which saw the state lose 44% of its dairy farms over the last decade. Concluding year, for the commencement time in state history, the number of dairy farms dipped below 7,000.

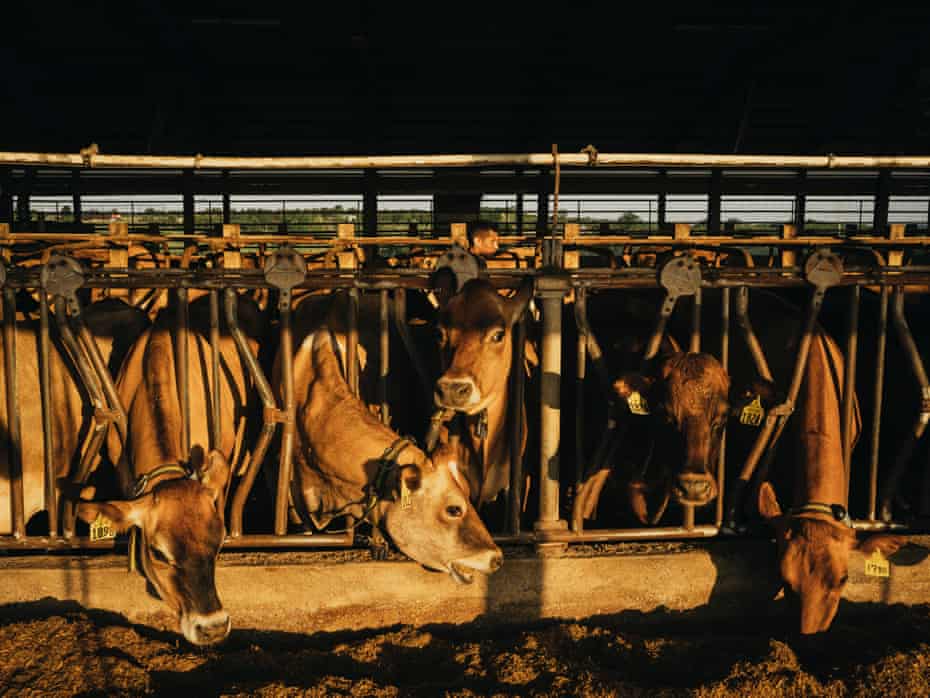

At the same time, milk product in the state has increased every year since 2004, and has set a new annual record each year since 2009, according to the Usa Department of Agriculture. In the last decade alone, Wisconsin has increased milk product past 25%. The number of operations declines, just as the number of cows per functioning goes up – 3% of Wisconsin farms at present produce roughly 40% of the state's milk. Milk produced on concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFO), or farms with more than about 700 cows but often housing thousands, is increasingly making upwards the state'due south overall milk product.

The number of large farms like this in Wisconsin has increased past 55% in less than a decade. A family unit-owned CAFO called Pinnacle moved into Green county in 2018, causing an uproar from local farmers and other residents.

Height milks 5,000 cows. It is endemic by Todd Tuls and his son, TJ, who oversees its 55 employees and the daily operations. Instead of collecting from 30 pocket-sized farmers across Dark-green canton, milk trucks can make but i stop – at Pinnacle – and they do, nine times a twenty-four hours.

Todd said he understood local misgivings. "I tin can see their anxiety, it's similar a Walmart coming into a small-town area and the local store is similar how is this going to impact me?" he said. "The one thing that bothers me the virtually is that people look at us as if we're a corporation and not a family business. Deep downwards inside nosotros are a family business," added Todd, who said he grew upwards on a California dairy farm with 4,400 cows at its height in the mid-1980s. His grandfather owned 3 dairy farms milking more than 3,000 cows in total in 1969, the year Todd was built-in.

He said the way he relates to his cows despite their size is role of their success, describing himself as "kinda like a cow whisperer". He argues that other farms missed opportunities to grow. "A lot of these farms that go out of business fail to adjust to the techniques and technology. Information technology's kinda similar if Ford or Chevy woulda only kept building the 1972 truck and not kept improving it."

'There ain't no future in dairy, none at all'

The Wallenhorsts bought a pocket-sized beefiness herd; like many former dairy farmers, they'll transition to raising steer for slaughter now. Only their barn is empty, dairy is done. "It's quiet, eerily quiet, for the first time in 50-some years. It's pretty strange," Ron said. "First couple days was difficult to walk in there."

Cory Bidlingmaier is a tertiary-generation auctioneer. "He was a nervous wreck, we really had to walk him through all of it," Cory said of Ron's state in the weeks leading upwards to the auction. But Cory has had plenty of feel with broken-hearted farmers. There take been weeks in recent years that Cory has washed four to v consummate dairy dispersals like the Wallenhorsts'.

Cory grew up in Dark-green canton: an expanse of silos and sky in southern Wisconsin that can be driven across eastward to west in a one-half hour. Few vehicles are seen other than the semi trucks that cut through the low hills hauling milk. Despite having 5 farms with 500 or more than cows, Green county notwithstanding has many of Wisconsin'southward small dairy farms, nigh 200, with between 50 and 100 cows, milked by the family.

The county went from being a highly competitive marketplace for generations to an area like and then many others in the state where also much milk is being produced. When the price of milk is downward, farmers milk more cows to compensate; if the milk price is upwardly, they milk more to capitalize. The excess of milk matches up with a plummet in consumption equally milk alternatives and h2o are chosen over milk. And the overabundance is worldwide, driving downwardly prices for farmers to the point they are barely breaking fifty-fifty or are losing money to produce it. On summit of that, a Dark-green county co-op of 25 local farms that accepts 3.5m pounds (i.6mkg) of milk to create 400,000 pounds (182,000 kg) of cheese a month unexpectedly shut down last autumn later 110 years due to pandemic-specific industry volatility. A shutdown like this is very rare, and left farmers scrambling for new processors to offload their milk.

Milk prices were at a tape high in 2014, then from 2015 on, went down. When prices are adept, small dairy farmers, able to finally turn a profit, make longstanding crucial repairs on the smaller scale, and do some meaning expansions on the large level. In early 2015 in Light-green county farmers were so confident in expanding that if yous wanted to put up a edifice, y'all were lucky if you could find an available contractor. But the proficient times never final.

"The milk cost only comes up a few times a yr, just plenty to tease 'em. So information technology drops again," Cory said. "When the farmers call us to auction their herd, they're saying 'Screw this, we're going to go piece of work in town or off the subcontract.' It affects and then many people. When a dairy goes out, the local feed store, the local hardware store, the whole local economy is affected." Larger farmers tin await across the state to find the best toll for anything they need.

Cory didn't grow up on a dairy farm, but like about everyone in Green county, being involved in the manufacture somehow was a given. He's seeing that change. "Information technology sucks for my x- and 12-year-former. When my uncle sold out a month ago, I made a betoken to become my boys over there to milk a cow so they can abound up and at least say they have done it," he said.

His job requires him to witness the final day of countless dairy farms; his outlook on the future of the industry reflects that. "In that location will be no family subcontract. The kids don't go into it, why would they? Get moo-cow shit all over you lot, work 19-hour days, and not accept a paycheck. Unless the family has former money, in that location ain't no hereafter in dairy, none at all."

Mark Stephenson, the director of dairy policy assay at the Academy of Wisconsin-Madison, said the manufacture definitely has a lot of challenges just is nowhere near extinction.

"We've produced record amounts of milk in the last twelvemonth or two. It'southward being consumed. Virtually of it domestically, but increasingly with exports," said Stephenson.

Last year, tankers were loading up milk and driving it straight to the subcontract's manure pit, opening the valve, and letting information technology go – milk dumping like this is quite extreme. Even so even in a year that started with unprecedented dumping, cows being culled, and milk sold at very distressed prices, then continuing with a milk price of $xiii per 100 pounds (£ix.32 per 45kg) of milk in the spring and summertime – which is less than the cost of production for virtually farmers – 2020 ended with a loftier demand for cheese. This was cheers in function to the government's pandemic food assist programs. By the finish of the twelvemonth the state's dairy farms again increased total production to thirty.7bn pounds (13.9bn kg) of milk. And on it goes.

Stephenson said farmers used to exist able to make a living with xv or 20 cows only a generation or two ago.

"You could hardly detect a farm like that now. That does non exist. At present we would expect at a 100-cow farm and say, 'Oh, isn't that quaint?'" he said. The compunction rate in Wisconsin for dairy farming is about 3–five% annually (in 2019 it was 10%), and as with farming across the country and specialties, it'southward hard to find new farmers to manus a family farm off to. Stephenson said, "Now we've got, at least, a couple generations that accept gotten to the point that they've never been on a farm and if they get there, they would just probably go, 'Oh boy. That smells bad.'"

The industry may have staying power, but as one made up of fewer, larger operations. Stephenson thinks large farms, those with more 500 cows, are the way of the future.

"Those quaint red barns that you are used to seeing on green hillsides with black and white cows in the fields, that just doesn't exist any more. Those barns over time volition begin to rot and fall down," he said. "That image that people have of what dairy farming is has to evolve into what is much more the reality now and those are big barns that house thousands of cows."

'Promise sustains the farmer'

"I bulldoze past Pinnacle a lot. It'southward icky. There'due south potholes everywhere because there's a semi in and out of there every hour," said Emily Harris, a fourth-generation farmer, of the CAFO that has moved into the county. "Information technology kinda makes you ill. Information technology's just a huge edifice, you don't fifty-fifty run into ane cow."

Emily and her married woman Brandi, both 39, live in Monroe, a minor metropolis in Green county near 40 miles due south of Madison. After 10 years, they stopped dairy farming on a Monday. "May 6 of 2019, the cows left," Emily said. Twoscore cows left on a omnibus trailer headed for farms in New York and Indiana. That Tuesday, Emily started her job at a nearby excavating visitor as an equipment operator. Emily cried for a week prior. Brandi held out until the twenty-four hours they left, then lost it. "They are your life, vii days a calendar week," she said.

They'd used farm equipment that looked similar antiques and went without making crucial repairs. They did everything they could to proceed milking, pushing hay into holes in the barn to stop the wind in peculiarly common cold years. They'd taken turns working off-farm jobs, as many subcontract families do.

"I think we fabricated money two of the years?" Emily asked looking over to Brandi, who shrugs. They'd had a decent organic contract, which by and large pay more conventional milk, but the new contract was all of a sudden going to be $twenty (£14) less per 100 pounds of milk, down from $37 (£26). Emily said, "We were only watching the milk price go down, downwardly, down."

Emily's advice for dairy farmers is blunt: "If they're under 300 cows, just quit. It's not worth it. You can't turn a profit whatsoever more. I retrieve the small-scale dairy farmer is gone. It's a sad deal."

Merely 20 minutes down the road, around the same fourth dimension the Harrises were starting their farm, Dan Truttmann, a 5th-generation farmer, was expanding his. "I wanted to go myself and my dad out of the milking parlor. We were at risk of wearing out, emotionally and physically," he said. He unceremoniously lifts one of near 20 barn cats out of an office chair side by side to desks near the milking parlor and the calf pen to check one of the dusty laptops keeping track of weight, feeding habits, temperatures, milk product and other vitals for every 1 of his 425 milking cows.

Before milk prices hit the downward trajectory they've remained on the last six years, dairy farmers ordinarily doubled their herds, equally Truttmann did, and but let their processor know they'd be shipping out more than milk. Truttmann said, "Now some of them are saying, 'Don't you dare send united states of america an actress load without our permission.'"

Truttmann, who is 53, has 9 employees helping himself, his brother, and his dad on the subcontract, which has been in his family since 1899. "Information technology's just non really likely that somebody with minimal education in the area could only buy a farm. You lot used to kind of recollect about that, similar, well, if you lot tin't do anything else, you tin e'er farm. Male child, that is not truthful at all today," he said.

He works up to 80 hours a week, getting up at five in the morning, an hour after 3,500 gallons (13,200 litres) of milk is picked up from his farm every day and taken to a local processor to be made into cheese for retail (which cushioned him from pandemic-specific blows to dairy farmers who sell to cheese processors for restaurants and schools). Green canton'south dairy farmers sell directly to cheese makers or co-ops, no one sells fluid milk.

Truttmann's three kids aren't interested in farming, but he's hopeful that a nephew may exist. He knows it's a hard sell – in good times, profit margins are about ten%. "When feed costs are high or hauling costs are shifted, all of a sudden there'south zippo left," he said.

His favorite chore on the farm is getting hours-old calves to bottle feed. He marches into a pen cradles the calf and patiently gets her to suckle – the play a trick on is putting her nose on his wrist, which makes her mouth open automatically. He wants her to get used to him, to understand this is her caregiver from day one.

Dorsum in his business firm, out of his rubber boots with his ankles crossed, he said, "I don't remember we're dissimilar from any other industry where as times change, you either change with them or get left behind. And that's the lamentable, hard reality of it. And even those that modernize are still at some hazard of being washed out. It's always a gamble." He paused. "Promise sustains the farmer. That's what the sign says on my back door."

-

This is part i of a ii-function series on America's changing dairyland. Function two will be published on Sunday

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/21/small-farms-vanish-every-day-in-americas-dairyland-there-aint-no-future-in-dairy

0 Response to "Dairy Farmers Are Left Behind Again"

Post a Comment